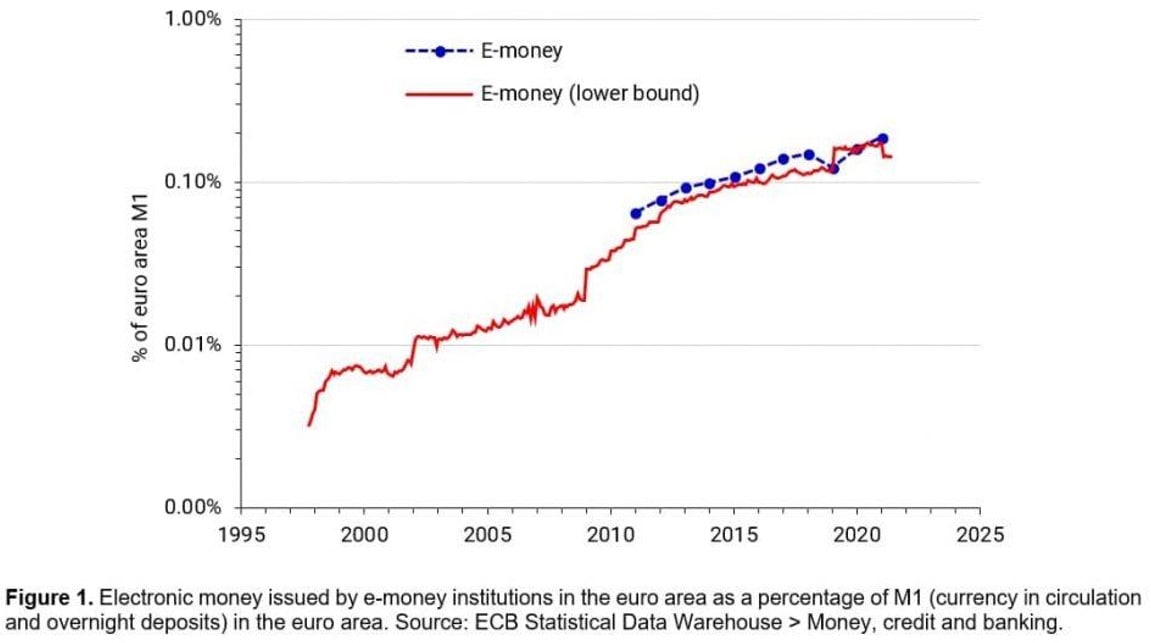

Since its introduction in late parts of 1990, the utilization of electronic money, or e-money was seen to increase with an exponential growth. This is evident on Figure 1 below:

One particular scenario was in the United Kingdom, having four percent (4%) of the country’s adult customers to use e-money as a payment method. Statistically, this is a three-percent (3%) increase as evaluated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Although this is a growth in nature, evidence shows and suggests that it is possible that most of these users do not really know that they are paying through electronic money, and they have minimal knowledge in differentiating e-money and deposits – and that of Electronic Money Institution (EMI) versus Bank, as a whole – regarding the security they are privileged with when it comes to the issuer’s inability to pay off debts.

The Financial Conduct Authority noticed this not long ago, and realized that they needed to publish an official letter to the Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of existing EMIs requiring them to be straightforward in educating their customers and clients about the difference between the mentioned methods.

Because of this issue, it is just right to provide more information about the topic and that is through this article. We will provide clarifications on the difference between deposits and electronic money from the customers’ point of view considering how traditional banking institutions and EMIs utilize and protect the customers’ funds and where these funds are being kept. Now, we can say that the EMI versus bank difference in terms of their balance sheets may be the deciding factor between e-money and deposits.

For those who have deposits and electronic money funds, and the EMIs, both established and new players in the e-money market, should find this article to be enlightening.

Who are the issuers of deposits and e-money?

The creation of an obligation (such as a debt) on the issuer’s balance sheet is the common understanding of issuance. Similar to how an institution that issues corporate bonds has a debt obligation on its balance sheet, an individual can have a mortgage loan liability, or a debt to the bank comes twenty to thirty years in time, whether they are aware of it or not. Deposits and electronic money are issued by the same entities that issue all other financial products.

Further, deposit issuance, frequently known as “acceptance,” is a tightly controlled operation mostly limited to financial institutions. According to the study by the European Banking Authority (EBA) in 2014 entitled “Report to the European Commission on the perimeter of credit institutions established in the Member States”, understanding that just a number of credit companies provide deposits are essential, and the same goes with the concept that just a number of credit companies issue deposits.

Regarding the first conception, certain credit companies are considered “credit institutions” even when they do not offer deposits but issue “other repayable funds” and give credits on their own funds.

Regarding the second conception, post office giro institutions (POGIs), usually referred to as “postal banks,” are a suitable example because several of them are known to be able to take deposits. This is according to the Article 1 (2) of Regulation (EU) No 1074/2013 and EBA in 2014, although they do not meet the criteria of being a “credit institution” in many nations.

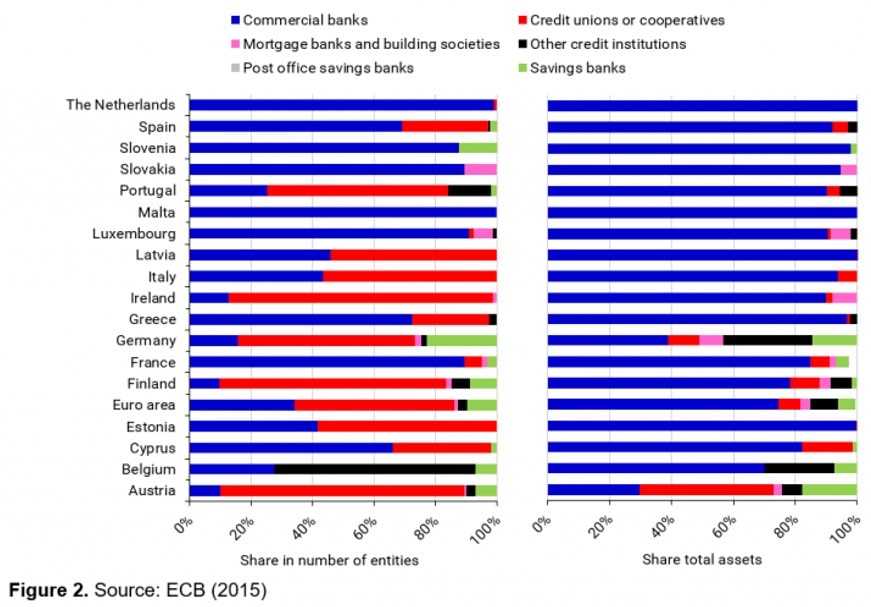

Full-service banks, lending institutions, mortgage banks, savings banks, and post office savings banks are some firms that make up the European Union’s credit institutions sector. In Figure 2 below, you can see how each country contributed to the total number of legal institutions or entities (on the left) and assets (right).

The types of companies that carry out electronic money issuance are more varied than those that carry out deposits. Electronic money providers are listed below:

- Electronic Money Institutions, or EMIs;

- Credit institutions (that is, banks);

- Post office giro institutions (also known as “postal banks”, such as the Post Office in the United Kingdom); and

- Countries’ central banks and public authorities at times when they are not serving as either a monetary authority or other public authority.

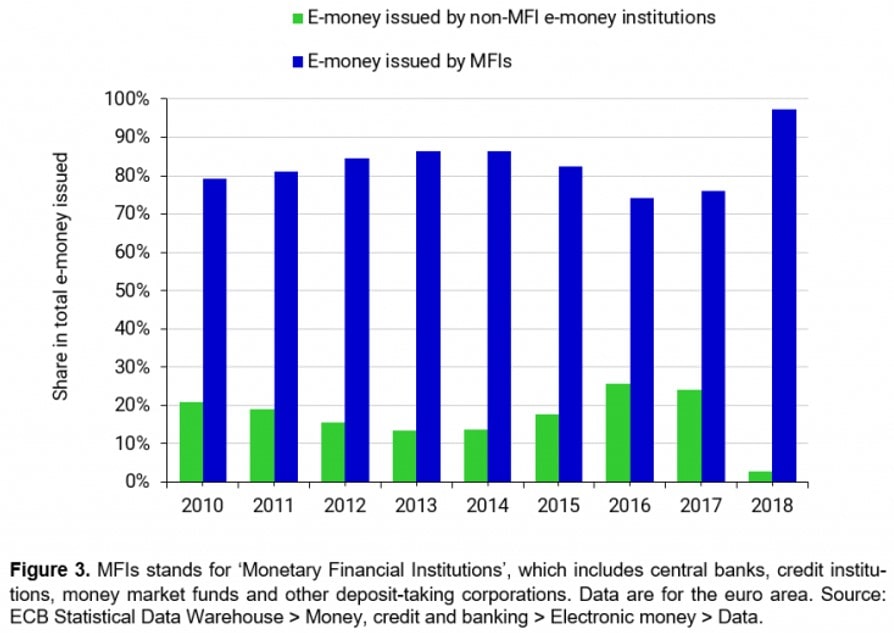

The larger parts of e-money sector are actually issued by credit institutions, which are a subset of monetary financial institutions (MFIs), as seen in Figure 3:

To put it in another way, as of right now, sight deposits and electronic money coexist on the liabilities side of the balance sheets of credit institutions.

For several instances, organisations that may have initially qualified as Electronic Money Institutions are ultimately given the deposit-taking license, joining the monetary financial institutions’ industry.

Revolut Ltd. is one illustration of this, since it has used its banking license from Lithuania to provide protected deposit accounts in Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia but not in the United Kingdom, where it still conducts business as an EMI.

Bank versus Electronic Money Institution: A Balance Sheet Comparison

It is required to first eliminate a common misconception about the nature of a current account to be able to recognise the distinction between the mentioned financial products and the subject of Electronic Money Institution versus Bank.

Following a poll done in Austria in 2020, sixty-eight percent (68%) of the two thousand (2000) survey participants think that bank savings and currency are guaranteed by gold. In 2009, a different study of two thousand (2000) Britons found that seventy-four percent (74%) of participants believed they were the rightful owners of the funds in their current account.

Both concepts are demonstrably untrue. Legal literature has long recognised that bank deposits are really loans to banks. In this sense, the word “deposit” might be deceptive since it implies relatively secure supervision, disposition of property, or reliance.

However, the deposit contract is often written such that the bank does not retain the depositor’s cash in custody; the monies are not set aside or designated. Instead, the bank is free to utilise the money however it sees fit and to mix (that is, commingling) them with its own funds as long as it returns the same amount to the depositor. That seems to be, the contrast between an electronic money institution and a bank is where the matter eventually comes down to.

As a result, when a depositor places funds in a bank, that individual is not the actual proprietor of that money. They are only one of the many customers the bank is in debt to.

The money a person has in an account with a creditor is the money that the company owes that person. It gives you a guarantee to pay it back, and that assurance is what our culture refers to as “money”.

Let us now look into the perspective of Electronic Money Institutions, or EMIs. In this respect, they are rather comparable since electronic money is both a credit claim made by the holder against the electronic money institution and a debt obligation made by the institution to the electronic money account holder. For efficient purposes, society is considering electronic money to be comparable to deposits from banks since both are utilized as payment methods for their purchases. The Electronic Money Institution guarantees to reclaim or move the money being demanded, just like how banks do it.

Looking at another crucial part of the industry, bank deposits and electronic money differ in one another, and the cause is how lending companies and electronic money institutions permit their balance sheets to be set up.

The unique characteristic of lending firms versus Electronic Money Institutions can be seen on the concept that even though lending firms can be mix the accounts provided by their clients with the companies’ own money, and even use both for their benefit (such as granting loans on their own funds), EMIs are required to separate their companies’ funds’ to that of their customers’, hence, keeping them segregated. Yes, Electronic Money Institutions can get a hold off their customers’ funds, nonetheless, they are not allowed to use it for their own objectives aside from pure business transactions like those that involve issuing and claiming of electronic money.

Meaning, in real life scenarios wherein banks keep one pound (GBP 1) in account (that is money reserves in central banks, or “nostro” account balances with other banking firms) for each ten pound (GBP 10) of electronic money debts (or usually noted as Fractional reserve banking, which means that a bank are permitted to use funds that would be unutilized or stagnant in order to gain profits through interest rates on new credits), Electronic Money Institutions should safeguard ten pound for each issued GBP 10 electronic money liabilities (in this case, they are required to keep a constant one is to one proportion or “parity”). This ruling is based on Articles 21 and 22 of The Electronic Money Regulations 2011 and Article 7(1) of Directive 2 Articles 21 and 22 of The Electronic Money Regulations 2011 and Article 7(1) of Directive 2009/110/EC009/110/EC.

In addition, contradictory to lending institutions in terms of deposits, Electronic Money Institutions are not permitted to allow loans from the accounts accepted in trading for e-money, and in case they do so, it should be a support and allowed only for those whose connected in performing the actual payments. This is stated in Article 32(2) of The Electronic Money Regulations 2011 and in Article 6(1) of Directive 2009/110/EC).

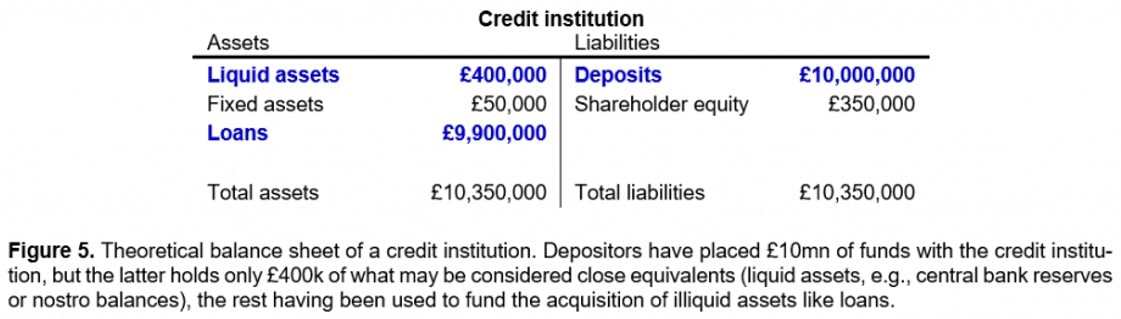

The explanation could be more understandable when you look at and compare the balance sheets of Electronic Money Institutions (on Figure 4) and credit firms (on Figure 5). A more restricted balance sheet is visible on EMIs’ than that of credit institutions’. It is required to have a parity to be maintained between electronic money obligations and safeguarded assets and this will bring them forth a lesser space for having other entries on the company’s balance sheets.

As previously stated, for each one pound worth of electronic money issued to clients, they must keep one pound in assets that are safeguarded and segregated from their company’s account. Usually, Electronic Money Institutions maintain protected accounts across other lending companies or even central banks and sometimes invest in a more liquid asset. It is also highly probable that there are instances wherein they utilise insurance to safeguard funds. Such a strategy is more known as “PSD Bond”.

Taking in the fact that by law, lending companies are permitted to allocate money from their customers, that amount can be utilised to fund more loans and can exit the banks, and are even replaceable by greater-yielding assets such as loans (such as transactions from banks, receiving deposits and payment of deposits at a lower rate than what they normally charge their lenders on credits). Figure five (Fig. 5) below is an illustration of what a balance sheet of a credit institution may look like:

In opposition to the situation of Electronic Money Institutions, the money owed by credit institutions to their creditors are largely supported by less liquid loans and just a minimum of liquid assets. Without any special support from the central bank, banks would not be able to fulfill their pledge to restore customers’ money even if they wanted to urge their banks to do so (letting them borrow reserves from central banks or cash from vaults on large amounts of volumes and more flexible terms).

On another note, Electronic Money Institutions have enough money on hand to cover a hypothetical unexpected demand for money withdrawals or transfers from all of their clients.

Here, things get a little more difficult because of where Electronic Money Institutions keep the money. The answer is, frequently, credit institutions (or banks) do not maintain an exact matching amount in funds that are similarly liquid (say for example with the central bank). The question of whether a client would lose the money stored in their electronic wallets if the bank where the Electronic Money Institution stores its secured cash failed is a source of significant debate (that results in insolvency).

According to the assessment, those who own electronic money carry out to lose funds since the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) does not apply to deposits made by financial institutions (including EMIs) with credit institutions (take into consideration that even if these deposits were protected, the protection would be ineffectual because they are only protected up to a maximum of eighty-five thousand pounds (GBP 85,000) and EMIs sometimes retain millions of dollars in client cash in pooled accounts.).

In any case, the fact that Electronic Money Institutions have all the funds necessary to meet a hypothetical unexpected demand from their clients in withdrawing or transferring money, and that in the event of being insolvent, these finances would be accessible to be dispersed to e-wallet owners, may help to partially describe in detail how it was that, in contrast to e-money, bank deposits are generally virtually assured by the country’s administration. The Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) in the United Kingdom provides depositor protection for sums up to GBP 85,000. This is again another distinction between a bank and an electronic money institution.

How about financial firms that print both paper money and electronic money? This is a somewhat uncommon matter, and not much has been published about it. According to the study, when credit institutions issue electronic money, separation restrictions are not applicable under United Kingdom legislation (neither, as was previously noted, when they make deposits) – they are solely applicable to banking institutions and electronic money institutions.

In the European Union (EU), not many banks issue electronic money, and their balance sheets are not well-documented either. There are several occurrences, though. Taking this as an example, studies have shown that the Luxembourg Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (the “CSSF”) permitted PayPal to utilise thirty-five percent (35 %) of the cash deposited to be electronic money holders to give credit. PayPal has a banking license in Luxembourg but seems to issue e-money solely.

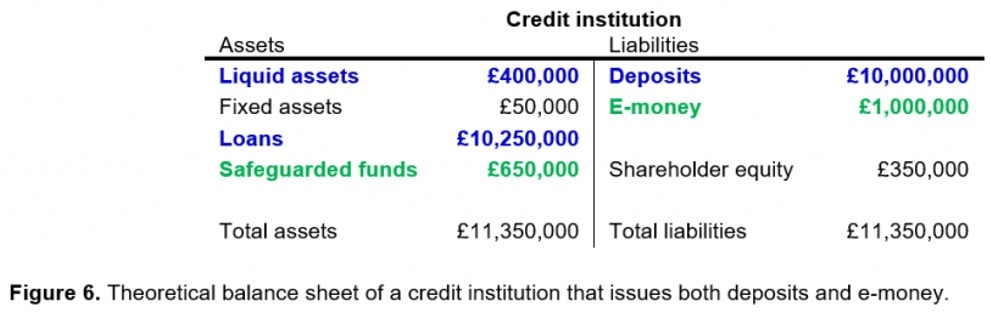

Researchers may imagine that the balance sheets of lending institutions that generate simultaneous deposits and e-money could resemble anything like this based on the scant data in Figure 6.

Result of Debate: E-money versus bank deposits

While deposit and electronic money loans (a guarantee to reimbursement on trend) issued by lending institutions are supported by borrowings and, to a lesser degree, bunker cash and reserves with the central bank that the credit institution is, electronic money obligations (another promise to full payment on trend) issued by electronic money institutions are supported on the financial assets of their balance sheets by an equivalent size of funds secured by the electronic money institutions in funds with lending institutions.

However, debts or obligations are not liquid enough, and creditors can fail to pay back a debt according to the initial agreement (or default). Depositors are likely to lose revenue if a bank fails due to widespread loan defaults because they are general lenders to companies. When these two financial products are established by the identical business, the very same guidelines are applicable.

How can COREDO help you?

If you are a beginner in the industry or a current Electronic Money Institution and have questions about Electronic Money Institutions vs. Banks, you might wish to contact our team at COREDO. You may visit our website at https://coredo.eu/.

Additionally, we can assist you in comprehending the practical and legal facets of safeguarding, securing accounts, and the e-money issuing industry more broadly. We are here to guide you not just through the intricate licensing process for electronic money institutions but also to assist you in comprehending how to grow your e-money company.